Guest House for Young Widows

Review by: Profile Editorial Team, 13/12/2019

I spent my childhood in 1960s Britain. World War 2 cast a long shadow and our play was often some form of war games, with Germans as the ‘baddies’. Films, books, comics all cast German soldiers one-dimensionally: they’d have an exaggerated love of ‘Fatherland’ and ‘the Fuhrer’, they were obsessive rule-followers, they lacked humour – this was all a child needed to ‘understand’ the enemy. We had a shared mindset we could work with, what was there to question? Then as we grew older and learned about the Holocaust, that knowledge naturally reinforced our childish prejudices. If anything it assuaged any doubts we might have otherwise held concerning the bombing of places like Dresden, any sense that there might be more than one story to emerge from the conflict.

Why am I talking about cartoon Germans? Because the role they carried out so helpfully in the Western imagination has now been occupied by jihadists, the preferred villain of the times. Perhaps the most depressing examples are to be found in contemporary genre fiction – particularly action thrillers - where all Muslims are devout, show very simple thought processes and, somehow, suicidal acts of terrorism are rendered without any internal conflict. Rather like the German soldier who loves his Fatherland and never questions authority, so the fictional Muslim is under the spell of his religion and never doubts the rewards he will gain in the afterlife. Our fictional Muslims are as crudely drawn as the SS soldiers of a previous generation.

This position is reinforced by the tabloid press – especially in Britain - which loves a pantomime villain like no other character. Nothing sells papers like a good baddie.

This is an important book, not least for the insight it provides into the comforting nature of religious orthodoxy

Guest House for Young Widows should be required reading for contemporary thriller writers and hack journalists, if only to show them what an authentic human voice sounds like. (It should also be required reading for a wider audience, but thriller-writers and hacks would make a great start).

The book follows a selection of real women who joined ISIS from homes in the Middle East and Europe – including Germany and Britain - and explores their home lives before they crossed over into making that decision, and on into its often miserable and tragic consequences. The author, Azadeh Moaveni, makes no claim to tell “the comprehensive story of all ISIS women”. Moaveni worked with the women she was able to engage with, drilling into the stories of their lives in sufficient detail to be able to almost novel-ise their stories. That this doesn’t quite read like a work of fiction is no great criticism: Moaveni takes time at intervals to remind the reader of what was happening in Syria and the wider world, and to analyse the effectiveness of anti-radicalisation programs (plot spoiler: she isn’t tremendously impressed). This, coupled with the large cast, breaks up the flow of the narrative but not excessively, and the effort to understand contemporary events is consistently worthwhile. It’s a deft balancing act between engaging the reader’s emotions through human testimony and infiltrating the reader’s analytical mind. I’m still processing much of the material in this book, a sure sign that some of the messiness of the real world has made its way in.

Guest House for Young Widows should be required reading for contemporary thriller writers and hack journalists, if only to show them what an authentic human voice sounds like

This is an important book, not least for the insight it provides into the comforting nature of religious orthodoxy. Those of us who no longer maintain religious observance can find piety baffling. It can be tempting to see religious faith in a negative manner, to make unfair or unkind assumptions. Seeing the world through the eyes of real people who derive comfort and certainty from their faith – particularly when life conspires against them – provides an antidote to cynicism, because over time we can come to see them as individuals, rather than as cartoons with cartoon characteristics. This, for me, is the real value of this book. I started to feel that I knew a few of these women, and had some sense of the motive forces which nudged them towards what turned out to be a calamitous decision.

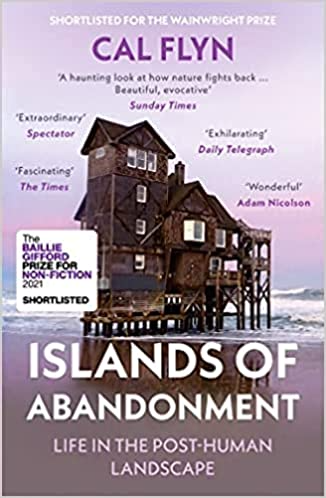

Guest House for Young Widows was shortlisted for the 2019 Baillie Gifford Prize for Non Fiction. To see the other shortlisted books, click here

Posted in: non-fiction

.jpg)