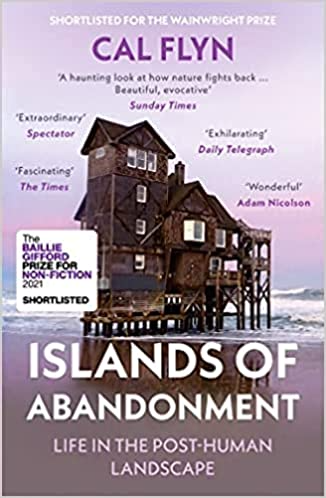

The Social Distance Between Us

Review by: Profile Editorial Team, 11/07/2022

We like to think that we are wise, worldly, experienced. That we know which way is up. It can be disconcerting – but valuable – to discover the depths of our ignorance about life in our own country. This book is a welcome kick up the pants.

Darren McGarvey rose to public attention through his first book, Poverty Safari, which discussed social policy in light of his own lived experience at the extreme edge of poverty and addiction in 21st century Britain. Poverty Safari posited the idea that well-intentioned policies and people nevertheless help to create the very conditions they seek to ameliorate – that we can’t understand poverty without also considering the agencies which are supposed to be helping. Poverty Safari was a powerful, between-the-eyes experience, and I was interested to see how Darren McGarvey’s perspective might have changed since becoming a media personality and achieving a much greater degree of financial security.

He addresses his own changing circumstances with characteristic honesty. It’s good to see that the even-handedness which so characterised Poverty Safari is still there – although McGarvey pins his colours firmly to a particular political mast, he goes out of his way to challenge his fellow travellers and also to be fair to other political belief systems.

Put simply, if all the best people are in all the top jobs, why is Britain such a f*****g bin fire?

There are three clear ideas in this book. The first is that Britain remains riven by class division, and that this is getting worse. The second idea is that policymakers are so distant from the daily realities of many – and particularly of people on the lowest incomes – that it is almost inevitable that policy will become muddled and ineffective. Worse – some of this government’s actions seem deliberately designed to enrich the already wealthy at the expense of the poorest in society. The third big idea is that the perennial media focus on the poorest as scapegoats for societal concerns is misplaced, and the real villains of the piece are the people at the top who consistently make bad decisions based on inadequate or flawed understanding of how ordinary people live. As McGarvey succinctly puts it: “Put simply, if all the best people are in all the top jobs, why is Britain such a f*****g bin fire?”

He is clear that this is an issue of social class. I never discuss class, indeed I don’t generally think about it as a discrete concept, so it’s jarring to be told that “. . . among you, there are those who claim that class does not exist. When people say they don’t believe in class, we must conclude they’ve arrived at such a position either because they do not see it or don’t want to see it”.

McGarvey provides an arresting view of the struggles faced by traumatised children in school. Virtually all of us have been to school and many of us are parents. These experiences inevitably colour our views about the education system, and may create a false sense that we understand what’s going on. We all hear stories about disruptive kids who make life difficult for the others. McGarvey’s own life experiences have given him great empathy with young people who’ve been trampled on by life. To many of us they might appear to be threatening, a nuisance or even a blight on society. Here’s how McGarvey sees such children: “I often use the analogy of Peter Parker, the secret identity of Spiderman, when he is first bitten with a genetically-engineered spider, which imbues him with special powers . . . what Parker refers to as his ‘spider sense’ which ‘tingles’ whenever danger is afoot. He often detects threats before they occur and takes evasive action to avoid injury and death. Hyper-vigilance, as experienced by those who have endured neglect and abuse, works in much the same way: victims develop an instinct for avoiding or mitigating harm. But take them out of the hostile environment and they become unable to regulate their spider sense . . . . Education selects for children who possess the ability, first and foremost, to emotionally regulate, to ask for help, to state their needs clearly . . . Under the duress of hyper-vigilance, a child will struggle to respond positively to the traditional social cues and behavioural incentives found in a classroom and this becomes the basis of their incremental exclusion – not simply from school but from society”.

Darren McGarvey takes us to some places we might not normally visit – his work as a rap tutor in prison, for example, or out on location with his TV programme. In each case his honesty, and willingness to expose his own vulnerabilities, is evident. He describes his own fear at being challenged to a rap competition in prison – fear that he will lose, and thereby lose face and be unable to work effectively with the young men he’s gone to support. He also describes an earlier time in his life when he was sacked from a similar role due to an alcoholic relapse which had left him incapable. Direct, honest self-truths which turn this from a polemic into something more valuable – a tour of a place we might have driven past but never visited.

Another lovely example of honesty is his description of a meeting with Tom Hunter, a self-made multi-millionaire. McGarvey describes his own difficulty in suppressing a sense of deference, the different way he treated Hunter compared with other people he had interviewed, the man’s charisma and presence and its impact on the crew. I found this disclosure – the class warrior owning up to deference – disarming. On a narrow path there was an unspoken understanding that Hunter would have the path while McGarvey traipsed alongside him in the mud, ruining his nice new trainers: “Why Tom never stepped on the grass and into the mud may appear inconsequential. But you will find a similar deference in royal and political correspondents. In how we fawn over celebrities. You’ll find it in the classroom and the courtroom and on the shopfloor, to varying degrees. And you’ll find it in elected officials when they deal with people like Tom. A reflexive deference not based on someone’s superior knowledge or insight . . . but far more primal in nature. This ‘instinct’ is perhaps the subtlest, most decisive advantage enjoyed by those of higher social classes. Only when you sense it in yourself, despite your radical pretensions, do you come to realise why a politician might struggle to speak plainly to the CEO of a tax-avoiding corporation, or a member of the royal family, or land and property owners with respect to thorny issues of fairness, justice and equality”.

A poor start in life is so statistically weighted towards poor outcomes throughout the remainder of a person’s life that a sense of inevitability pervades: “Care leavers make up 25 per cent of the homeless population and almost 25 per cent of the adult prison population . . .Thirty-nine per cent of care leavers aged 19-21 were known not to be in education, employment or training, compared to around 13 per cent of all 19- to 21-year olds”

McGarvey speaks honestly about his own experiences with addiction, and the seductive power which drugs and alcohol hold over people. This, for me, is one of the unique aspects of Darren McGarvey’s work – the only sermonising is about the dysfunctional systems and agencies which regularly fail the people he is writing about. Contrast this with the media, with tropes in fiction, the shorthand versions of humanity we consider when we think of, for example, a homeless person with addiction and mental health issues. McGarvey has no difficulty in identifying with the poverty-stricken people he meets, acting as a bridge.

Proximity is McGarvey’s key theme. Or rather, the lack of proximity of people in power to the people who are most likely to be affected by their decisions. A book can’t remediate a lifetime spent looking the wrong way but it can at least highlight the significance of the problem and give us fresh eyes to see what’s all around. For this reason alone, The Social Distance Between Us should be required reading for MPs.

This book was written while Boris Johnson was Prime Minister, while Covid raged and locked us all down for prolonged periods, and while the poorest in society suffered and died in far larger proportions than the better-off among us. All are targets for McGarvey’s anger, but he reins it in, keen to win over middle-class readers who might never have considered social class as a key factor in the life journeys of millions of fellow Brits. This is an important book – different in tone to Poverty Safari and much more exhaustive in its research and examination. Only time will tell which of these books has the greatest impact on policy makers. Despite enjoying a measure of financial security, Darren McGarvey has retained both his passion for helping those who have been left behind and his ruthless self-honesty. I can’t help feeling that Darren McGarvey’s best work is yet to come.

Posted in: non-fiction