Communing with Homer

Review by: Profile Editorial Team, 02/09/2020

If the past is a foreign country, prehistory sometimes feels like an alien planet. We know our culture came from somewhere, yet it can be difficult to feel connected to the people we learn about from archaeology. Their belief systems just seem too distant.

And yet we’re drawn to their stories. Ancient storytelling still works its magic – suggesting that the pattern for a story to ‘work’ hasn’t really changed in thousands of years. Which raises other questions – how far back in time would we have to go before we find humans who didn’t tell stories? Would we still recognise them as human?

Today we look at two wonderful books which cast fresh light on Homer’s epic poems.

‘The Mighty Dead’ is Adam Nicolson’s personal exploration of Homer. And this really is a personal exploration – Nicolson leaves enough of himself in these pages to feel like a friend. More on that in a moment.

Who was ‘Homer’? The Iliad and The Odyssey are traditionally attributed to a poet of that name, but as Nicolson takes us wandering it becomes clear that ‘Homer’ is a shorthand for an entire oral tradition, perhaps an army of poets who have helped to shape the stories we know today.

The Mighty Dead reads like the best kind of radio documentary, moving through space and time at will. Nicolson visits the library at Alexandria where some of the lines were edited to better suit contemporary sensibilities, and then moves on to such apparently disconnected locations as Serbia, Crete, the Hebrides, searching for modern transmitters of old poetry in a bid to understand what happens to an epic poem when it passes from generation to generation. The surprising answer to that question might be: not much. Nicolson recounts the Hebridean poet Duncan Macdonald telling a tale – ‘The Man of the Habit’ – to folklorists on five separate occasions – in 1936, 1944, 1947, 1950 and 1953. The 1953 folklorists had a transcription of his 1950 recitation. Nicolson tells us ‘Scarcely a word was different from the printed version they held in their hands . . . one or two interjections that were different and some synonyms changed, but on the whole seven-thousand-odd words of the story were exactly as he had told them three years earlier. On analysis, all five of his versions were as good as identical’.

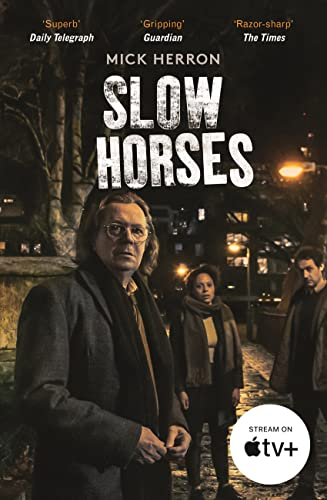

So if an oral tradition can preserve the integrity of the text, what does this tell us about the date of origin? How far back into prehistory do these stories really go? Nicolson presents a convincing case for the Bronze Age, at least in their mentality, the warrior code, the weapon-worship evident in Homer. And on this topic – the meaning of the blade - Nicolson invites the reader in to share in one of his own most devastating experiences. The anecdote – which I shan’t reveal here – is delivered with such disarming simplicity and directness that the relationship between author and reader changes at that moment. Adam Nicolson tells a simple story of his own reaction and response to an armed attacker. It’s a shocking moment – I found it almost unbearable – and it reminds us that these stories aren’t children’s cartoons but the bragging of a real warrior race, our own brutal ancestors - the very essence of toxic masculinity. Nicolson reminds us that “Iliadic behaviour echoes through modern urban America . . . American gang members talk about themselves, their ambitions, their idea of fate, the role of violence and revenge, in ways that are strangely like the Greeks in the Iliad . . . Crime itself on these streets becomes moral, and revenge a form of justice”.

Revenge and honour. Masculinity doesn’t get much more toxic than this. Which brings us neatly to The Silence of The Girls, by Pat Barker. If you’re familiar with The Iliad you’ll recall that it’s about a row between two warriors on the same side – King Agamemnon and Achilles, the greatest fighter in the Greek camp. They all take women as their trophies but Agamemnon is forced to return his when her priest father calls down a plague on the camp. To replace her, Agamemnon pulls rank and takes the woman who had been ‘allocated’ to Achilles, the beautiful Briseis. Achilles goes on strike and the tide turns against the Greeks.

The Silence of the Girls tells the story of The Iliad from Briseis’ viewpoint. The book starts with the mighty Achilles leading the attack on Lyrnessus, the city where Briseis had been a queen – and now would become just another woman to be distributed to a soldier. Seeing war from a woman’s perspective shifts the frame: this battle is for survival, not glory or fame. Every glorious war song is also a tale of rape, murder, mass starvation for the survivors and the destruction of cultures.

The Silence of the Girls is a brilliant accompaniment to the Iliad, and would make the perfect introduction for newcomers to Homer. Pat Barker is no stranger to war – her Regeneration Trilogy took the First World War as its setting – and here she brings us face to face with the helpless victims of war in a manner which is unsentimental, honest and direct, building a bridge between modern sensibilities and the thoughtworld of a Bronze Age warrior culture.

At a time when violence lingers just beneath the surface we need to understand our nature, and the character of violence like never before. War is not new: it is transmitted through our genes and our culture. The victims of war have no voice in our histories, and precious little in our literature. The genius of the Silence of the Girls is that it doesn’t preach or seek to shock, it simply tells a story, and the reader’s empathy does the heavy lifting.

Pat Barker has given a voice, not only to a beloved character from fiction but also to the dispossessed and brutalised throughout history. What a gift to the world.

Posted in: non-fiction